By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

The earth’s surface is two-thirds covered with water, as we all know, and many of us live on or near the water. Those of us that live in seaside communities know that every year we lose a friend or neighbor to the sea. Every time I hear about a loss, I am always reminded of the hymn Eternal Father, Strong to Save, the first verse of which is below:

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidd’st the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

Unfortunately, too many people head out to sea with nothing more than a prayer to help them if they encounter trouble. We could have saved many people if they only had a method of communicating their emergency to the Coast Guard or to another boat nearby. The purpose of this column is to discuss the different means of communicating that a vessel is in distress so that recreational boaters can decide which method is best for them.

The Station Galveston Flotilla of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary operates out of the USCG Station Galveston base on Galveston Island. They aid the Coast Guard by providing maritime observation patrols in Galveston Bay; by providing recreational boating vessel safety checks; and by working alongside Coast Guard members in maritime accident investigation, small boat training, providing a safety zone, Aids to Navigation verification, in the galley, on the Coast Guard Drone Team and watch standing.

Visual Distress Signals

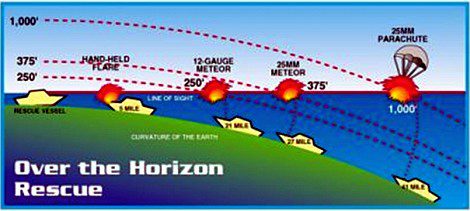

Visual distress signals are the only method required by the Coast Guard for communicating that a recreational vessel is in distress. As the illustration shows, the chances of your pyrotechnic visual distress signal being seen by another vessel depends on the type of signal. Depending on the weather and visibility, the range of detection is from around five miles for a handheld flare to up to 41 miles for a 25mm rocket with parachute.

Meteor flares and parachute flares not only have a visual characteristic, but they also have a report that can be heard as well. If you fire off a meteor flare without a vessel in your sight, then you are taking a chance that there is a vessel close enough to see your flare. The loud report gives you two chances that the flare will be seen or heard. In the off chance that a flare is heard but not seen, the recommendation is that you follow up the first flare immediately with a second flare. A person hearing a report behind them will turn toward the noise and possibly see the second flare as a verification that they heard a visual distress signal. If you see a flare while on the open sea, how do you let the other vessel know you saw it? Simply fire off a flare of your own in answer to the original signal, and then head toward the other boat as best you can determine the direction. If you need further guidance, you can fire off another flare and hope you receive an answering flare. If you are a boater equipped with a radio, then immediately notify the Coast Guard whenever you see a flare at sea. Important information to give the Coast Guard is your position, the direction of the flare from you, and how high above the horizon the flare rose if it was a rocket flare.

To improve the Coast Guard’s ability to respond and increase the chance of rapidly locating a mariner in distress, a technique known as the “Fist Method” has been developed to assist in accurately determining the position of the flare in relation to yourself, the reporting source.

The Fist Method:

To estimate the distance of a flare from your position, hold your arm straight out in front of you and make a closed fist. Hold the bottom of your fist on the horizon with the thumb side pointing up. Picture in your mind the flare that you saw, compare the height of the flare at its peak to your fist. Was it 1/2 fist? A whole fist? Two fists?

By using this method, the Coast Guard can estimate how far away the flare is from you. The Coast Guard will ask you several more questions to narrow down the position of the flare.

The Coast Guard recommends that you do not keep expired rocket flares aboard or shoot them off, as they may fail to launch and explode instead. The Coast Guard recommends that you dispose of expired pyrotechnics at your local fire station or see if your Coast Guard station can use them for pyrotechnic demonstrations. If rockets are part of your visual distress signal package, add a pair of safety goggles and leather gloves to the kit.

VHF/FM Marine Radio

I highly recommend that boat operators invest in a DSC (Digital Selective Calling) VHF/FM marine radio. Handheld (walkie talkie style) radios, which have a transmit power of up to 5 watts, can be used to reach the Coast Guard up to 20 miles from any US shore. Console mounted marine radios typically have 25 watts of transmit power, and with a full-size antenna can reach much farther than a handheld radio.

If you are going to depend on your VHF radio for distress communication, don’t be like Robert Frost who took the road less traveled. Operate in areas in which you are likely to encounter other recreational boats or commercial vessels. VHF/FM marine radio is what is called “line of sight” radio. This means radio antennas must be line of sight from each other in able to communicate. The US Coast Guard has a system called Rescue 21. It is a system of tall radio towers that allows us to talk to ships and boats using VHF radios up to 20 miles from any U.S. seashore. In many cases that range is extended, but ship-to-ship communications are much more limited and are very dependent on antenna height. Transmission wattage is another critical factor. While it is generally accepted that a handheld 5-watt radio routinely transmits distances of 5-10 miles, 25-watt radios, which also have a higher antenna, can transmit ship to ship up to 20 miles.

Most newer VHF radios are DSC enabled. While some radios have built in GPS, others must be linked to a GPS in order to automatically transmit your coordinates. There is a special cable that must be used to connect your radio to your GPS. A DSC enabled radio requires that you obtain an MMSI (Maritime Mobile Service Identity) number and program it into your radio. A new radio with DSC will not operate until an MMSI is programmed into the radio. You only get one chance to enter the correct number into your radio, so take care before hitting the Accept button. You have to confirm the number after you enter it, but if you enter the wrong number both times then your only choice is to have the radio shipped back to the manufacturer to be reset. When you apply for your nine-digit MMSI number, the information you give in the application is what is sent to the Coast Guard whenever you activate the system.

Most newer VHF radios are DSC enabled. While some radios have built in GPS, others must be linked to a GPS in order to automatically transmit your coordinates. There is a special cable that must be used to connect your radio to your GPS. A DSC enabled radio requires that you obtain an MMSI (Maritime Mobile Service Identity) number and program it into your radio. A new radio with DSC will not operate until an MMSI is programmed into the radio. You only get one chance to enter the correct number into your radio, so take care before hitting the Accept button. You have to confirm the number after you enter it, but if you enter the wrong number both times then your only choice is to have the radio shipped back to the manufacturer to be reset. When you apply for your nine-digit MMSI number, the information you give in the application is what is sent to the Coast Guard whenever you activate the system.

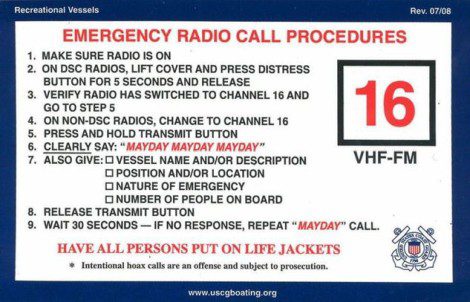

It does not matter what channel your radio is on when you activate the Distress signal. The system transmits your MMSI number to the Coast Guard on Channel 70 (a non-voice channel) and then immediately changes your radio to Channel 16. When you activate the Coast Guard Rescue 21 System by lifting the switch cover and pressing the emergency button for five seconds, the Coast Guard will call you on Channel 16 and ask the nature of your emergency. Because an untrained person may be required to use the radio in an emergency, you can do them a favor by giving everyone aboard a briefing on where the radio is, how to activate the Distress system, and how to use the microphone. Go one step further and put the Emergency Radio Call Procedures sticker right next to your radio.

Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) or Emergency Position Indicator Beacon (EPIRB)

While the VHF marine radio is a significant upgrade from visual distress signals, it, too, has its limitation, that being distance from shore, due to its line of sight only operation. The next step up is to use a satellite-based Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) or Emergency Position Indicator Beacon (EPIRB). The biggest difference between these two devices is that EPIRBs are registered to a boat while PLBs are designed for use by an individual. EPIRBs are mounted on the boat itself, while PLBs are usually worn on a PFD or carried in a pocket or “ditch bag” (a bag of emergency gear you can grab in a hurry). PLBs must be manually activated while a Category 1 EPIRB activates when submersed. A Category 2 EPIRB can also be manually activated. Newer model PLBs and EPIRBs have dual transmitting. They transmit at 406 MHz to the satellite detection system and they have a 121.5 MHz swept tone homing signal. Other more advanced EPIRBs also have an Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmitter for localized rescue.

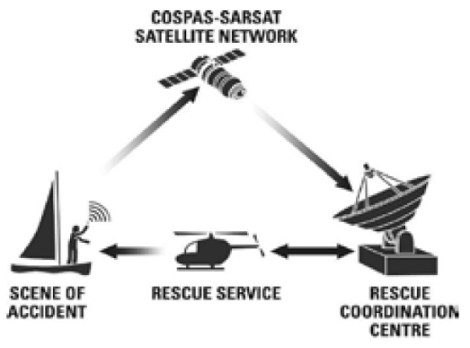

When triggered, the PLB or EPIRB transmits a unique serialized ID to the Cospas-Sarsat MEOSAR satellite system which can pinpoint your location anywhere on the earth’s surface. This is typically within minutes but can be up to 45 minutes depending on satellite coverage. The Rescue Coordination Centre (RCC) then forwards the details of the emergency to the appropriate local Search and Rescue (SAR) services.

Satellite Phones and Satellite Messaging Devices

While PLBs and EPIRBs will always result in someone coming to the rescue, they have their limitations. They cannot indicate the nature of an emergency- they can only indicate that a person or vessel is in distress.

The SMS messaging device (orange) here can be used to send text messages, or it can be linked to your smart phone for using it as a satellite phone. The blue phone is a standard satellite phone. Satellite phones vary in cost. Some messaging devices and satellite phones allow you to inactivate their plans when not being used and then activate them for use during a voyage. The phones are not cheap to buy or use, but the messaging devices can do the trick and offer much better affordability. Not every phone or messaging device connects to every communication satellite, so you must ensure that the phone you choose will work in the geographic area in which you plan to operate. I have two friends who use the messaging devices and are quite happy with them. One friend has traveled from Houston through the Panama Canal several times, and he used his messaging device to keep in touch with us. The other uses his device on fishing trips out to the snapper banks.

The SMS messaging device (orange) here can be used to send text messages, or it can be linked to your smart phone for using it as a satellite phone. The blue phone is a standard satellite phone. Satellite phones vary in cost. Some messaging devices and satellite phones allow you to inactivate their plans when not being used and then activate them for use during a voyage. The phones are not cheap to buy or use, but the messaging devices can do the trick and offer much better affordability. Not every phone or messaging device connects to every communication satellite, so you must ensure that the phone you choose will work in the geographic area in which you plan to operate. I have two friends who use the messaging devices and are quite happy with them. One friend has traveled from Houston through the Panama Canal several times, and he used his messaging device to keep in touch with us. The other uses his device on fishing trips out to the snapper banks.

Summary

There are four basic categories of devices used for sending a distress signal. First, and the only method required by the Coast Guard, is the pyrotechnic visual distress signal. Their range of operation is from about five to 41 miles and they depend on another vessel to see the signal and come to the rescue or call the Coast Guard. The second category is the radio, in particular for recreational boaters, the VHF/FM marine radio, with a range of 5 to 20 miles. If you do not venture farther than 20 miles from shore, this is your best bet for quick emergency assistance. Third, PLBs and EPIRBs use satellite notification of vessels in distress. The downside is that they do not transmit the nature of the distress. They will always result in a rescue effort. Finally, satellite phones and messaging devices allow you to make both routine contact with someone or allow you to transmit a distress message. The only caveat is to ensure the satellite phone or messaging device will work in the geographic area in which you intend to operate.

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org. Questions about the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[Apr-26-2022]

Posted in

Posted in