By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

By Bob Currie, Recreational Boating Safety Specialist

U. S. Coast Guard Auxiliary Station Galveston Flotilla

Most recreational powerboats have what is called a planing hull. The other major type of hull is called a displacement hull. Ships have displacement hulls. Boats with planing hulls start out in the displacement mode, but as speed reaches a critical point the boat will rise up over its bow wave and skim across the surface of the water rather than push its way through. There is also a type of hull called a semi-displacement hull. A boat with a semi-displacement hull can rise up on plane, but only at a significant cost to fuel efficiency. This column will deal solely with the aspects of a full planing hull.

The Station Galveston Flotilla of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary operates out of the USCG Station Galveston base on Galveston Island. They aid the Coast Guard by providing maritime observation patrols in Galveston Bay; by providing recreational boating vessel safety checks; and by working alongside Coast Guard members in maritime accident investigation, small boat training, providing a safety zone, Aids to Navigation verification, in the galley, on the Coast Guard Drone Team and watch standing.

How a Planing Hull Works

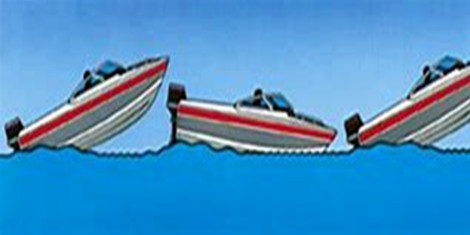

A typical planing hull has little or no keel and is flat toward the transom. This flat portion of the hull is designed to trap air and create the lift required for a boat to get up on plane. Planing is not limited to power boats. Surfboards also have planing or semi-planing hulls, and most sailing dingy hulls can achieve the planing mode. That said, planing hulls require a high power to weight ratio. Planing hulls in general have only been around for 100 years or so. At rest a boat’s weight is supported solely by buoyancy. As the boat moves through the water, it creates both a bow and stern wave. With a planing hull, as speed increases those two waves merge and become one. At some speed the bow of the boat will rise up on that combination wave and plane- that is, skim across the top of the wave. At that point the boat is lifted by hydrodynamic force and it overcomes the buoyant force. A boat on plane generally has about one third to two thirds of its hull out of the water. One caveat: the more of the hull you have out of the water, the less maneuverability you have. You can plane up higher than it is safe to operate.

Getting up on Plane

A lot of boaters call this the hole shot. Their goal is to get up on plane in X number of feet, and they do that by ramming the throttle forward wide open. While this can be exciting, it places an unnecessary strain on the engine and the hull. The better method is to trim the engine down and slowly advance the throttle. It won’t take but a few extra seconds to reach plane using this method, and it is not only safer but it is also more fuel efficient. When you ram that throttle forward, the bow rises significantly and you do not have good control of the boat’s steering due to the centrifugal forces set up by the prop.

Difficulty in Reaching Plane

Most difficulties in reaching the planing mode are due to weight. An overweight boat often cannot reach the planing mode. Your capacity plate tells you the maximum weight your boat can hold; the capacity plate number includes persons, equipment, and engine weight. If you exceed that weight chances are you will not be able to plane your boat. If you find that you cannot plane your boat even though you are carrying the same number of people and the same equipment with which you have always been able to reach plane, try turning on your bilge pump. You may have water in your bilge (a lot of water if you forgot to put in your plug). Water weighs 8 pounds to the gallon, and it doesn’t take many gallons to stop you from reaching plane or at least making it difficult to achieve plane.

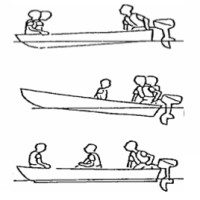

Another common problem is weight distribution. If everyone is at the stern of the boat, you will have difficulty rising up on plane. Your boat manual gives you the ideal seating chart for passengers. Some boats even have stickers that show proper weight distribution. Uneven distribution can affect the boat in a few ways. Planing is one problem, handling is another, and fuel efficiency is a third item affected by poor weight distribution.

Engine trim is another factor that could be preventing you from achieving plane. The proper trim for starting a boat is trim all the way down. You need the entire boat in the water to create both a strong bow and stern wave. If your trim is up, the bow will rise, and you will not create the combination bow-stern wave necessary to reach plane.

Over-propping can affect your ability to reach plane. The prop number tells you how far a prop will advance through a block of gel in one revolution. I have a 19-inch prop on my boat. That means if the prop is placed in a box of gel and turned one revolution, it will move 19 inches through that block of gel. That is just a reference point because water is not like gel. One turn of that 19 inch prop might not push me one inch through water. With that 19 inch prop I am able to achieve 6500 rpm with full trim and just me in the boat. That equates to around 52 mph. If you do the math using gel, 6500 rpm equates to 116 mph. So, if you divide achievable speed by theoretical speed, you get 44 percent efficiency (52/116).

Let’s say I replace the 19 inch prop with the next size up, a 21 inch prop. The theoretical speed (through gel) using the same 6500 achievable rpms is 129 mph. But now with the 21 inch prop I can only turn 6000 rpms. Substituting 6000 for 6500 in the equation gives me a theoretical speed of 119 mph. If I use the same theoretical efficiency of 44 percent, that gives me a maximum speed of 52.5 mph. Boy that was a waste of money for a new prop! In real life, propping up will make it harder to plane, and often results in a lower achievable rpm due to overloading the engine, and thus a lower top speed. If your boat was underpropped to begin with and you went up to the next prop, you would increase your maximum speed, but you would also most likely make it harder to achieve plane. It’s like trying to start a car with a manual transmission in second gear.

So, going up in prop number theoretically can increase your top speed, but not necessarily so, but it will also affect your ability to get up on plane. The best gauge is to use what your engine manufacturer says is your maximum rpm (it will usually be a range rather than a single rpm). My engine manufacturer says maximum rpms is 6000 to 6500 rpm. If I can obtain that range with my boat properly trimmed, then I probably have the right prop for my boat. If I can only obtain 5500 rpm, then I am probably over-propped. If my boat will exceed 6500 rpm, then I am probably underpropped.

Porpoising. Shouldn’t it be dolphining?

Porpoising. Shouldn’t it be dolphining?

Porpoising

So, you are cruising along nice and smoothly with your engine trimmed up to the maximum, and your boat suddenly starts porpoising. Porpoising is the rhythmic rising and falling of the bow and is an indication that the engine is trimmed too high. Porpoising is named after the wrong marine mammal. That’s right- those aren’t porpoises we see out in the Gulf of Mexico. They are dolphins. Dolphins breath air like we do, sort of. They have a blow hole in their head, and as they swim through the water they exhale out the blow hole and as they break the surface they quickly inhale their next breath. So, now you see them as they break the surface, and now you don’t as they swim below the surface, and a few seconds later they break the surface to get another breath. The cure for light, rhythmic porpoising is to slightly trim your engine down until the porpoising stops. Reducing speed slightly will also help.

Porpoising is also a symptom of poor weight distribution, especially when there is too much weight at the stern. The safest way to adjust the distribution  is to come to a complete stop before asking passengers to move forward or change sides, as the case may be.

is to come to a complete stop before asking passengers to move forward or change sides, as the case may be.

A violent type of porpoising occurs whenever you cross another boat’s wake at the wrong angle. The proper angle to cross another boat’s wake is 45 degrees. If you cross at a higher angle, you can cause your boat to begin porpoising violently in ever increasing frequency, with the bow rising higher with each cycle. The key is to use the proper angle to cross the wake in the first place, but if you find yourself violently porpoising, you need to reduce speed or even stop. Trimming is not the issue here. When your boat is violently porpoising you can injure passengers who may be thrown about, and you can also over-stress your hull and cause damage. On welded boats you can break welds, and on fiberglass boats you can induce cracks in the hull. If the violent porpoising becomes too severe you could pitch pole your boat.

Another cause of porpoising is structural. If you leave your boat in the water all the time, you can develop hull growth that can cause your boat to porpoise. The hull growth can grab the water as you get on plane and pull the bow back down. If trim adjustments, weight re-distribution and speed reduction don’t cure your porpoising, inspect your hull. If it is not smooth and clean, that could be why you are porpoising.

Coming Off Plane

If you are cruising along on plane and desire to come off plane, then you need to do so in a manner that doesn’t throw your passengers around or cause equipment such as ice coolers to shift. That means you should let your passengers know that you are “coming down” so they can hold on as you slowly reduce throttle. Sudden reduction in throttle can cause injuries, damage equipment, and cause your wake to catch up with your transom and flood your boat. Flooding/swamping was the number 2 top cause of boating accidents in 2020 (the latest year for which we have statistics). Falls overboard was the number 5 top cause of accidents, and you can sure toss someone overboard with an abrupt stop.

Summary

The plain truth is that getting a boat up on plane, operating on plane, and coming off plane requires some experience and finesse to do it properly. You need to take it slowly until you learn the operating characteristics of the boat and engine combination, and you must adjust your technique for the number of passengers and amount of equipment you have in the boat.

For more information on boating safety, please visit the Official Website of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Division at www.uscgboating.org . Questions about the US Coast Guard Auxiliary or our free Vessel Safety Check program may be directed to me at [email protected]. SAFE BOATING!

[Nov-9-2021]

Posted in

Posted in

I saw 2 boats this summer Porpoising and having a long roster tail. I’m sure his gas mileage suffered along with a bouncing ride.